If you want to buy drugs or guns anonymously online, virtual currency Bitcoin is better than hard cash. Canny speculators have been hoarding it like digital gold. Now the world's leading bankers are even talking about as a rival for real money. How does it work, where can you get it and is it the future.

A sign above a bar in Germany. Photograph: Alamy

The past weeks have seen a surprising meeting of minds between chairman of the US Federal Reserve Ben Bernanke, the Bank of England, the Olympic-rowing and Zuckerberg-bothering Winklevoss twins, and the US Department of Homeland Security. The connection? All have decided it's time to take Bitcoin seriously.

Until now, what pundits called in a rolling-eye fashion "the new peer-to-peer cryptocurrency" had been seen just as a digital form of gold, with all the associated speculation, stake-claiming and even "mining"; perfect for the digital wild west of the internet, but no use for real transactions.

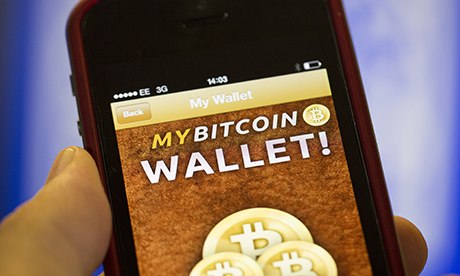

Bitcoins are mined by computers solving fiendishly hard mathematical problems. The "coin" doesn't exist physically: it is a virtual currency that exists only as a computer file. No one computer controls the currency. A network keeps track of all transactions made using Bitcoins but it doesn't know what they were used for – just the ID of the computer "wallet" they move from and to.

Right now the currency is tricky to use, both in terms of the technological nous required to actually acquire Bitcoins, and finding somewhere to spend them. To get them, you have to first set up a wallet, probably online at a site such as Blockchain.info, and then pay someone hard currency to get them to transfer the coins into that wallet.

A Bitcoin payment address is a short string of random characters, and if used carefully, it's possible to make transactions anonymously. That's what made it the currency of choice for sites such as the Silk Road and Black Market Reloaded, which let users buy drugs anonymously over the internet. It also makes it very hard to tax transactions, despite the best efforts of countries such as Germany, which in August declared that Bitcoin was "private money" in which transactions should be taxed as normal.

It doesn't have all the advantages of cash, though the fact you can't forge it is a definite plus: Bitcoin is "peer-to-peer" and every coin "spent" is authenticated with the network. Thus you can't spend the same coin in two different places. (But nor can you spend it without an internet connection.) You don't have to spend whole Bitcoins: each one can be split into 100m pieces (each known as a satoshi), and spent separately.

Although most people have now vaguely heard of Bitcoin, you're unlikely to find someone outside the tech community who really understands it in detail, let alone accepts it as payment. Nobody knows who invented it; its pseudonymous creator, Satoshi Nakamoto, hasn't come forward. He or she may not even be Japanese but certainly knows a lot about cryptography, economics and computing.

It was first presented in November 2008 in an academic paper shared with a cryptography mailing list. It caught the attention of that community but took years to take off as a niche transaction tool. The first Bitcoin boom and bust came in 2011, and signalled that it had caught the attention of enough people for real money to get involved – but also posed the question of whether it could ever be more than a novelty.

The algorithm for mining Bitcoins means the number in circulation will never exceed 21m and this limit will be reached in around 2140. Already 57% of all Bitcoins have been created; by 2017, 75% will have been. If you tried to create a Bitcoin in 2141, every other computer on the network would reject it as fake because it would not have been made according to the rules of currency.

The number of companies taking Bitcoin payments is increasing from a small base, and a few payment processors such as Atlanta-based Bitpay are making real money from the currency. But it's difficult to get accurate numbers on conventional transactions, and it still seems that the most popular uses of Bitcoins are buying drugs in the shadier parts of the internet, as people did on the Silk Road website, and buying the currency in the hope that in a few weeks' time you will be able to sell it at a profit.

This is remarkable because there's no fundamental reason why Bitcoin should have any value at all. The only reason people are willing to pay money for the currency is because other people are willing to as well. (Try not to think about it too hard.) Now, though, sensible economists are saying that Bitcoin might become part of our future economy. That's quite a shift from October last year, when the European Central Bank said that Bitcoin was "characteristic of a Ponzi [pyramid] scheme". This month, the Chicago Federal Reserve commented that the currency was "a remarkable conceptual and technical achievement, which may well be used by existing financial institutions (which could issue their own bitcoins) or even by governments themselves".

The First Bitcoin ATM, in Canada. Photograph: REUTERS

The First Bitcoin ATM, in Canada. Photograph: REUTERS

It might not sound thrilling. But for a central banker, that's like yelling "BITCOIIINNNN!" from the rooftops. And Bernanke, in a carefully dull letter to the US Senate committee on Homeland Security, said that when it came to virtual currencies (read: Bitcoin), the US Federal Reserve had "ongoing initiatives" to "identify additional areas of … concern that require heightened attention by the banking organisations we supervise".

In other words, Bernanke is ready to make Bitcoin part of US currency regulation – the key step towards legitimacy.

Most reporting about Bitcoin until now has been of its extraordinary price ramp – from a low of $1 in 2011 to more than $900 earlier this month. That massive increase has sparked a classic speculative rush, with more and more people hoping to get a piece of the pie by buying and then selling Bitcoins. Others are investing thousands of pounds in custom "mining rigs", computers specially built to solve the mathematical problems necessary to confirm a Bitcoin transaction.

But bubbles can burst: in 2011 it went from $33 to $1. The day after hitting that $900 high, Bitcoin's value halved on MtGox, the biggest exchange. Then it rose again.

Speculative bubbles happen everywhere, though, from stock markets to Beanie Babies. All that's needed is enough people who think that they are the smart money, and that everyone else is sufficiently stupid to buy from them. But the Bitcoin bubbles tell us as much about the usefulness of the currency itself as the tulip mania of 17th century Holland did about flower-arranging.

History does provide some lessons. While the Dutch were selling single tulip bulbs for 10 times a craftsman's annual income, the British were panicking about their own economic crisis. The silver coinage that had been the basis of the national economy for centuries was rapidly becoming unfit for purpose: it was constrained in supply and too easy to forge. The economy was taking on the features of a modern capitalist state, and the currency simply couldn't catch up.

Describing the problem Britain faced then, David Birch, a consultant specialising in electronic transactions, says: "We had a problem in matching the nature of the economy to the nature of the money we used." Birch has been talking about electronic money for over two decades and is convinced that we find ourselves on the edge of the same shift that occurred 400 years ago.

A Bitcoin wallet on a smartphone. Photograph: Bloomberg via Getty Images

A Bitcoin wallet on a smartphone. Photograph: Bloomberg via Getty Images

The cause of that shift is the internet, because even though you might want to, you can't use cash – untraceable, no-fee-charged cash – online. Existing payment systems such as PayPal and credit cards demand a cut. So for individuals looking for a digital equivalent of cash – no middleman, quick, easy – Bitcoin looks pretty good.

In 1613, as people looked for a replacement for silver, Birch says, "we might have been saying 'the idea of tulip bulbs as an asset class looks pretty good, but this central bank nonsense will never catch on.' We knew we needed a change, but we couldn't tell which made sense." Back then, the currency crisis was solved with the introduction first of Isaac Newton's Royal Mint ("official" silver and gold) and later with the creation of the Bank of England ("official" paper money that could in theory be swapped for official silver or gold).

And now? Bitcoin offers unprecedented flexibility compared with what has gone before. "Some people in the mid-90s asked: 'Why do we need the web when we have AOL and CompuServe?'" says Mike Hearn, who works on the programs that underpin Bitcoin. "And so now people ask the same of Bitcoin. The web came to dominate because it was flexible and open, so anyone could take part, innovate and build interesting applications like YouTube, Facebook or Wikipedia, none of which would have ever happened on the AOL platform. I think the same will be true of Bitcoin."

For a small (but vocal) group in the US, Bitcoin represents the next best alternative to the gold standard, the 19th-century conception that money ought to be backed by precious metals rather than government printing presses and promises. This love of "hard money" is baked into Bitcoin itself, and is the reason why the owners who set computers to do the maths required to make the currency work are known as "miners", and is why the total supply of Bitcoin is capped.

And for Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss, the twins who sued Mark Zuckerberg (claiming he stole their idea for Facebook; the case was settled out of court), it's a handy vehicle for speculation. The two of them are setting up the "Winklevoss Bitcoin Trust", letting conventional investors gamble on the price of the currency.

Some of the hurdles left between Bitcoin and widespread adoption can be fixed. But until and unless Bitcoin develops a fully fledged banking system, some things that we take for granted with conventional money won't work.

Others are intrinsic to the currency. At some point in the early 22nd century, the last Bitcoin will be generated. Long before that, the creation of new coins will have dropped to near-zero. And through the next 100 or so years, it will follow an economic path laid out by "Nakomoto" in 2009 – a path that rejects the consensus view of modern economics that management by a central bank is beneficial. For some, that means Bitcoin can never achieve ubiquity. "Economies perform better when they have managed monetary policies," the Bank of England's chief cashier, Chris Salmon, said at an event to discuss Bitcoin last week. "As a result, it will never be more than an alternative [to state-backed money]." To macroeconomists, Bitcoin isn't scary because it enables crime, or eases tax dodging. It's scary because a world where it's used for all transactions is one where the ability of a central bank to guide the economy is destroyed, by design.

For Bitcoin developer Hearn, that's not a concern. "Bitcoin's monetary policy would only be relevant if it were to be adopted by an entire economy, which isn't going to happen any time soon."

Already, alternatives based on Bitcoin have sprung up: for instance, Litecoin speeds up transaction processing and Freicoin introduces measures to stop people hoarding their money, but both are essentially the same technology, "forked" from the original. There's even nothing to stop a nation state declaring its own version of Bitcoin as legal tender.

So even if the currency of the future looks like Bitcoin, it might end up being a distant successor of the pioneer. "Is the technology of Bitcoin a window into the future?" asks Birch. "Yes. Is Bitcoin itself? No."

Source : The Guardian

Les services de carrier billing se multiplient, simplifiant le paiement et poussant les géants high-tech à nouer des partenariats pour intégrer ces fonctionnalités.

Les services de carrier billing se multiplient, simplifiant le paiement et poussant les géants high-tech à nouer des partenariats pour intégrer ces fonctionnalités.