Avatar pushes computer graphics to the very edge of what's possible, particularly in IMAX 3D. Cameron's no stranger to game-changing special effects, with The Abyss he had a hand in creating first fully digital 3D water effect, in Terminator 2: Judgment Day he had the first CGI human character with realistic movement, and in Titanic he used the advanced the rendering of flowing water. Avatar may be another step, but before we take it, we're looking back on Avatar's ancestors. This is how we got here, these are the movies that made Avatar and other computer generated special effects possible. It all started right here…

The Thief of Baghdad (1940)

The First Use of Chroma Key

The First To Use Animated 3D Graphics

Tron (1982)

Extensive Use of 3D CGI

Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan (1982)

The Genesis Effect

Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988)

Realistic CGI/Human interaction

Jurassic Park (1993)

Photorealistic CGI Integrated With Animatronics

Toy Story (1995)

First Feature Film To Use Only Computer-Generated Imagery

The Matrix (1999)

Bullet Time

Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (2001)

Photorealism and Live Action Principals In An All Digital Feature Film

Lord of the Rings Trilogy (2001-2003)

The Polar Express (2004)

First Feature Film With All Motion Capture Characters

Immortel (ad vitam), Casshern, Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow, and Sin City (2004-2005)

Use of The Digital Backlot

Photorealistic Motion Capture Using Virtual Camera System, and Facial Expression Cap Cameras

We have officially arrived at the here and now. A movie revolution took place at the end of 2009 - potentially offering as big a leap in our viewing experience as the change from black-and-white television to colour.

James Cameron, the film director who pushed technical effects to the limit with the blockbuster Titanic in 1997 -11 Oscars and the highest-grossing revenue of all time- , and ushered in the dawn of action films with '80s classics such as Terminator and Aliens, has unleashed the film he has been hoping to make for nearly 20 years.

Behind Avatar : Science, Technology, Art and Design

Underscoring this two and a half our epic lie unparalleled technological, scientific and artistic achievements, including the invention of a novel 3-D film camera, the complete biological and linguistic realization of a virtual world, and flawlessly integrated art direction and conceptual renderings. Many people’s post-viewing reaction will be, “How did they do that?!” ScriptPhD.com is proud to present a special Avatar preview that includes behind-the-scenes secrets and a review of the must-own companion design book The Art of Avatar. Before you go see the movie, get to know it.

Fresh off of astronomical success with Titanic—11 Oscars and the highest-grossing revenue of all time—James Cameron could have done anything. He was King of the World, remember? Any film, any project, the sky was the limit. Instead, he disappeared, only to reemerge in 2005 to propose a new big-budget blockbuster to 20th Century Fox. They funded a $10 million 5-minute prototype for Avatar, but hesitated green-lighting full production, citing the 153-page script (first conceived in 1995), ambitious new video technology, and a story producers feared would alienate audiences. Only when Disney expressed interest in the film did they give Cameron a full go-ahead. The result is a movie with a final budget of over $230 million that required four years’ of full-time work to complete. Avatar is a sweeping epic that takes place on fictitious Pandora, a distant moon in the Alpha Centauri-A star system that has been colonized by humans in the year 2154. Discovery of an abundant precious ore, unobtanium, that might solve Earth’s energy crisis leads corporate and military interests to infiltrate the ranks of a native population of humanoids called the Na’avi. Because of a toxic atmosphere, human “drivers” link their consciousness to genetically engineered avatar models—50% human DNA, 50% Na’avi DNA. Jake Sully, a paraplegic ex-Marine, has been called to take his dead brother’s place for scientific exploration of Pandora’s ecosystem, biosphere and indigenous peoples. Inadvertently enveloped into learning the Na’avi culture and ways, Jake soon falls in love with the Princess Neytari and becomes caught in a battle between his own people and the virtual world he has adopted. Avatar, however, transcends whatever story or theme one imagines to define it. It is a pinnacle of scientific and technological innovation, an ode to its filmmaker’s vast travels (earthly and underwater) and intergalactic fascinations, and a harbinger of a filmmaking style that will redefine 21st Century cinema. “This film integrates my life’s achievements,” Cameron said in a New Yorker profile earlier this fall. “It’s the most complicated stuff anyone’s ever done.”

The Technology

•Performance Capture

Motion capture and computer-generated imagery (CGI) are not new to film. Motion capture (or green screen technology) was first introduced by Cameron for Total Recall, with the first CGI human movements added later for Terminator 2. It is, however, inherently limiting to the size and proportions of the human body, in particular the actor of the character being portrayed. The eyes can’t be moved, for example, and makeup often inhibits actor performance. CGI is traditionally done by placing reflective markers all over an actor’s face and body, which are then interpreted by computer technology to create digitized expressions for the CG character. However, the gulf between human and CG expression, referred to as the “uncanny valley”, is often quite noticeable. To bridge the two and create the first truly seamless hybridized CGI, Cameron and his team developed a new “image-based facial performance capture”, requiring the actors to wear special headgear rig equipped with a camera. With cameras placed just inches from their face, actors’ every muscle contraction or pupil dilation was captured and digitized, creating astounding emotional authenticity to their Na’avi avatar counterparts. “If Madonna can be bouncing around with a microphone in her face and give a great performance,” Producer Jon Landau said in a New York Times interview, “we thought, ‘Let’s replace that microphone with a video camera.’ That video camera stays with the actor while we’re capturing the performance, and while we don’t use that image itself, we give it to the visual-effects company and they render it in a frame-by frame, almost pore-by-pore level.” The scope of clarity and precision of the head-rig allowed for a much larger capture environment than ever before, a bare stage called the “Volume”, six times larger than any previous capture environment.

James Cameron supervising digital effect production for Avatar. Photograph by Art Streiber.

•Digital animation

State-of-the-art animation renderings for Avatar were done by Peter Jackson’s New Zealand-based digital-effects studio Weta Digital. A team of talented artists transferred basic renderings (more on this below) into photo-real images, particularly using new breakthroughs in lighting, shading, and rendering. “I’ve seen people looking at Avatar shots, being convinced they are somehow looking at actors in makeup,” Jackson says. The realism was extended to each leaf, tree, plant and rock, which were rendered in WETA computers. Additionally, a team of artists, headed by Academy Award winner Richard Taylor, designed the props and weapons for the Na’avi and humans. All of this digital design took over one year to complete and took up over a petabyte, one thousand terabytes, of hard drive space!

James Cameron shoots a scene from Avatar using new 3D camera technology. Image courtesy of 20th Century Fox.

•Stereoscopic 3D Fusion Camera System

As far back as ten years ago, James Cameron had wanted to develop a 3D camera. At that time, the concerted goal was to use it to shoot a gritty Mars movie that would act as an emblem for space exploration (Cameron is on the advisory board of NASA). At this time, stereoscopic 3D cameras were the size of washing machines and weighed 450 pounds. The challenge issued to production partner Vince Pace was to develop a lightweight, quiet camera capable of shooting in both 2D and 3D. The result of over seven years of hard work was the groundbreaking new Fusion Camera System, the world’s most advanced 3D camera. It facilitated an almost flawless merger between live action scenes and CG scenes. Most of the live-action scenes were shot in Wellington, New Zealand on sets constructed by a massive team of 150 contractors. Live-action sets included the link rooms (where the humans transported to their Na’avi avatars, the Bio-Lab, the Ops Center military operations area, and the Armor Bay military stronghold, which housed all the weapons and transport units.

•Virtual Camera/Simul-Cam

Tying together the 3D and CG technology of visualizing the film were two new Cameron intermediary inventions: the virtual camera and the simul-cam. The virtual camera, used by Cameron in the Volume motion capture stage, wasn’t actually a camera at all. Looking like a video game controller, it simulated a camera that was fed CG images by supercomputers surrounding the Volume. This allowed amplification of each small adjustment on the virtual production stage, from camera movement to actor interaction, to gauge the overall effect on the final big-screen cut. The simul-cam fed, in integrated real-time, CG characters and environments into the live action Fusion 3D camera eyepiece, allowing Cameron to direct virtual scenes on Pandora the same way he would a live-action scene.

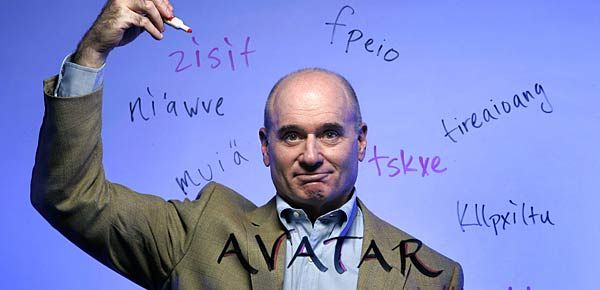

Dr. Paul Frommer, surrounded by Na'avi words he created for Avatar. Photo ©2009 Los Angeles Times.

The Language

Not satisfied with merely creating an otherworldly planet and its native beings from scratch, James Cameron set about equipping the Na’avi humanoid tribe with a language of their own. Audiences will be delighted in the authenticity—all communication on Pandora is shown through subtitles befitting a foreign film. Ever the mindful scientist, Cameron hired USC professor and linguist Dr. Paul Frommer to engineer the dialect from scratch, resulting in a respectable, self-sufficient vocabulary of about a thousand words bound by a consistent sound system, grammar, orthography, and syntax. In an extensive interview with Vanity Fair, Dr. Frommer says that Cameron approached him as far back as 2005, when Avatar was going by a code name of Project 880. As with every other aspect of this film, Cameron’s genius micromanagement provided Dr. Frommer with the basics of the sound and structure he was looking for. “I didn’t start from absolute ground zero,” said Frommer, “Because James Cameron had come up with, in the early script, maybe 30 words. Most of them were character names, but there were a couple of names of animals. So at that point I had a sense of some of the sounds that he had in his ear and it reminded me a little bit of some Polynesian languages.”

In addition to painstakingly working on the syntax for over five years, which he compiled into a pamphlet entitled Speak Na’avi, Dr. Frommer worked closely on-set with Avatar actors to ensure proper pronunciation and phonetic differences between native Na’avi speakers, and their human avatar contrasts. Beyond the film, Dr. Frommer is not done developing Na’avi, in the hopes that it might take off like Klingon did post-Star Trek. “I’m still working and I hope that the language will have a life of its own,” the professor said in an interview with the Los Angeles Times. “For one thing, I’m hoping there will be prequels and sequels to the film, which means more language will be needed. I spent three weeks in May, too, working on the [Avatar] video game for Ubisoft, which is the name of a French company.” (The Hollywood Reporter recently posted a terrific interactive preview of the video game.)

The Science

A technically-adept filmmaker such as James Cameron could have been satisfied with simply allowing his 3D team to virtualize Pandora, especially since most of the world is synthesized from scratch. Instead, Cameron, himself an accomplished diver and the brother of an engineer, painstakingly, some would say obsessively, set about populating the moon with flora and fauna using rigorous scientific methodology. He enlisted the help of UC Riverside botanist Jodie Holt, who became an expert on Pandora’s vegetation and mentored Sigourney Weaver in portraying a botanist in the film. Each leaf, plant, creature, and weed was given an original Na’avi name, a Latin taxonomy, a biological description, population and occurrence, ecology and ethnobotany. Click here to watch a brief interview with Dr. Holt about her role in assembling the biological vision behind Padora’s ecosystem.

Incidentally, all of the information I have written about above and more is being compiled by the film’s writers, producers and directors into a 350-page tome called Pandorapedia, to be made available later this winter. Until then, for curious fans and film devotees looking to gain insight into the artistic development process of Avatar, ScriptPhD.com recommends the stunning design book The Art of Avatar, reviewed below.

Cinema, Meet Art + Design

The Art of Avatar ©2009 20th Century Fox and ABRAMS Books. All rights reserved.

While planning and technology were essential nuts and bolts of its cinematic architecture, they alone do not constitute the blueprint or heart and soul of a film such as Avatar, especially considering the ambitious multi-thematic plots and visual realm. Like any innovative, transformative concept or endeavor, Avatar began and ended with the simple sketch. In a gorgeous, 120 full-color illustration rich companion volume, The Art of Avatar, written by Lisa Fitzpatrick, James Cameron and Peter Jackson, provides a fully transparent visual documentation of the first phases of the development and conceptualization of Avatar. The book’s 200+ works of art include compositions by renowned film artists (Rob Stromberg, Wayne Barlowe, Ryan Church, Ben Proctor and Cameron himself), descriptive script excerpts, commentary and a guide to each component’s realization process. As Fitzpatrick notes in the book’s copy, “it is the artist behind the technology that makes the images of this book, and ultimately the movie, so remarkable.” Having seen both (review here), ScriptPhD.com wholeheartedly agrees.

Suspension of disbelief. The cornerstone of any creative compact between a film and its audience. A compulsory foundation for escaping into imagined worlds and embracing its characters and adventures. Notwithstanding this axiom, Avatar still represents a giant leap forward in the world of filmmaking, according to Peter Jackson, Oscar-winning visionary behind The Lord of the Rings and recently District 9. “Every once in a while, we will see a movie that transcends cultural barriers, genre and taste—a film that lives on in the minds of the audience, years after the fact, a film with a story, characters and dialogue so memorable that it creates its own mythology,” Jackson notes in his foreword to The Art of Avatar. A project of such magnitude can initially seem insurmountable. Executive Producer Jon Landau said he felt like a NASA engineer in 1961 when President Kennedy announced we were heading for the moon—only the moon in question was Pandora.

Much of the initial design was jump-started by Cameron, himself a talented illustrator and meticulously descriptive screenwriter. His own sketches included largely preserved concepts of Na’avi clothing and signature physical appeararance, including a complete design of the heroine Neytiri’s painted face. The humans’ habitat the Venture Star included an 11-page document on how the ship functioned, with physics and engineering details such as light-speed calculations, pod dynamics, engine thermodynamics and architectural plans. Cameron’s Avatar script treatment—a plot and content synopsis—included visual primers such as glowing phantasmagorical forest, purple moss [that] reacts to pressure, rings of green light, dreamlike, surreal beauty that allowed artists to create accurate renderings of Pandora’s biosphere (see below picture).

Pandora's breathtaking panorama, observed by the avatar Jake and his native love interest Neytiri.

Content in The Art of Avatar is smartly divided into categories, including transport, science, gadgetry, and biology. Transport and gadgets, including the Valkyrie shuttle and the Samson untilitarian vehicle, are designed with layouts and specificities worthy of industry standards. Particularly impressive to The ScriptPhD were the details and accuracy of early renderings of the home base biolab, clearly conceived by a man with a profound respect for science. Illustrations of labs are laid out to look like actual labs, with incredible attention to the link unit allowing the humans to transform into their avatars and the incubator tubes housing avatars, by far the most challenging prop for Weta Digital to produce. As an example, the Armored Mobility Platorm (AMP) suit used by military to safely roam around Pandora was designed by TyRuben Ellingson to be functional and accessible (good viewing capacity, easy maneuvering, flexible joints, rearview mirrors). Pictured below is just one of a multi-page design book for the AMP suit alone!

Engineering design of the AMP military suit.

The Na'avi princess Neytiri with the avatar Jake. Cameron describes her in the script: "She watches, only her eyes are moving. She is lithe as a cat, with a long neck, muscular shoulders, and nubile breasts. And she is devastatingly beautiful-for a girl with a tail." ©2009 20th Century Fox.

Biology illustrations are largely split categorically by flaura/fauna and creatures. Pandora’s many unique forests, the Home Tree and Floating Mountain key to the film’s plot, the illuminated foliage, and bioluminescent Fan Lizards and Woodsprites—original Cameron creations—each get individual renderings. In several pull-out pages, the creative process is gradual. Neytiri, for example, started as a pencil sketch, evolved into a clay figurine, then 3D artwork, and finally a screen version. Most interesting to note was the process of creating the original creatures of Avatar. The most critical and symbolic of these was the Banshee, a heroic creature that enjoys a lot of screentime in the film. It is meant to be a metaphor for the eagle, and, as a transport vehicle for the Na’avi, to represent them as a flying culture. Take a look at the transition between an early automotive biomechanical concept sketch by designer Wayne Barlowes and final color digital drawings.

Early concept drawing of the Banshee bird, meant to employ biomechanical form and function.

The final color illustration.

In an exclusive epilogue, James Cameron confesses that he feverishly wrote Avatar in 1995 over the span of just three weeks, fueled largely by his own imagination, every piece of fantasy art ever created, and his rigorous, extensive experience under the ocean. While certain things were specific to Cameron’s preferences—namely the Thanator and Viper wolf drawn by himself—all others were achieved through a sometimes turbulent, always rewarding collaborative process with a talented team of artists, designers, scientists and technologists. “The goal [of the design] became to mix the familiar and the alien in a unique way,” Cameron states. “To serve the metaphor and create a sense of familiarity for the audience, but to always be alien in the specifics.”

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire